TightWind is written by Kyle Baxter. Stay Hungry. Stay Foolish.

The Party After Trump

October 17th, 2016We are only a few weeks away from the 2016 general election. Unless the polls are fundamentally wrong, Donald Trump will lose, and he will lose by a significant margin. Trump and the movement he represents will go down to ignominious defeat.

I am no fan of Hillary Clinton. I find her corruption to be repulsive, her exposing classified information dangerous and characteristic of her narcissism, and her platform to be little other than more government as the solution to every problem.

And yet, when Trump loses next month, we should all have a small moment of celebration. Trump is uniquely dangerous to our nation, and to the world, and we are fortunate that he appears too incompetent and appalling an individual to defeat as poor a candidate as Hillary Clinton.

That moment will be short indeed.

After Trump loses the election, what Trump represents will not fade. While Trump’s outright racism, affection for authoritarianism, and desire to subordinate the United States to Russia are new, the seeds of Trumpism precede him. Trumpism was not created whole cloth by Trump. He saw a large contingent of the GOP that was frustrated with the Republican Party’s failure to repeal the Affordable Care Act and to slash immigration, after the GOP made promises to its voters that leaders knew they could not keep while President Obama was in office, and a GOP in Congress that was largely unresponsive and uncaring to the economic difficulties of Americans; a contingent of voters still obsessed with the idea that President Obama was not born within the United States and therefore is ineligible to be president; a president that used an executive order to force through changes to an immigration system he did not have the votes in Congress to make; a contingent of voters that distrust the media and increasingly the GOP, and who were increasingly defined by no beliefs besides opposition to immigration, and to Democrats, separate from disagreements over ideology. Instead, politics calcified into little more than fighting the enemy for no other reason than because they are the enemy and must, by definition, be defeated.

Racism on the right did not begin with Trump’s announcement in June 2015 that he would run for president. Despite many Republicans’ protests that the GOP is the party of Lincoln, the party has had a long history of racism within it. In the last decade, many Republicans did not just see Barack Obama as a poor candidate for president, but someone that is not eligible to be president, and that does not have our interests at heart. The birthers based their skepticism on no evidence besides chain emails, his name and skin color. John McCain, to his lasting credit, pushed back against it when confronted with it at a campaign event during the 2008 race, but Republicans generally did not forcefully confront it. Many on the right oppose welfare spending based on blatant anti-black racism, arguing that blacks who live in poor neighborhoods have no excuse for being poor but their own failings, and that those failings may be caused by characteristics of blacks. Those arguments are based on a willful misunderstanding of our history and are a re-packaged version of the idea that blacks are inferior to whites. The right’s opposition to illegal immigration itself, although not inherently racist in nature, certainly is supported by some based on bigotry against Hispanics. “They’re taking our jobs” is little more than xenophobia, even if there are good reasons to oppose lax immigration rules, both legal and illegal. Trump did not create racism in the GOP. He exploited it.

The appeal Trump made to Republican voters in the primaries was that he recognized their plight, and would make America great again. That slogan is integral to his appeal, because it speaks to every complaint this group of voters has. It implies that “real Americans” (and all that phrase implies) were screwed over by globalists in both parties that pushed for free trade deals which, in their mind, gutted the American economy of well-paying industrial jobs for lower-skilled workers, and for lax immigration rules and enforcement of them, which allowed millions of illegal immigrants to enter the U.S. and steal their jobs. It implies that we must re-assert security within the country against foreigners, the immediate descendants of immigrants, and in our cities. It implies that America has been weakened and reduced by a black president, someone that isn’t “really” American, and whose loyalties lie with foreigners. And it speaks to their desire to “take” control of the country from the “elites”—the people in the Republican and Democratic parties, in the media, and who run corporations; the people, they believe, that conspire to send jobs overseas and bring foreigners here to water down the power of “real” Americans (whites).

That slogan, along with his call for building a wall across the U.S.-Mexican border, deporting all illegal immigrants, banning Muslims from entering the United States, slapping stiff tariffs on all trade with China, penalties for companies that move jobs overseas, and asserting “law and order” in our cities, speak directly to this group of voters. The bare nature of it—the illegal immigrants, the Mexicans and the Chinese stole your jobs, and I’m going to stop them—along with his insistence on describing illegal immigrants as “drug dealers” and “rapists”—was directed at them: The United States is now a third-world nation, your life is terrible, and it is not your fault. Our country is terrible because of the Mexicans, because of the Chinese, and because of the conniving elites that plotted to screw you over so they could get wealthy. He stiffened his appeal by pointing out that he knows what the elites do, because he has participated in their corrupt system. He turned his own corruption into an asset with the crowd that was increasingly angry with our institutions.

Making his appeal that way also framed his opponents as part of the problem. They are all officeholders, and did not deliver for this group of voters. In his telling, they not only did not deliver (because they are ineffective politicians), but also plotted amnesty for the hated illegal immigrants. They are simultaneously incapable and nefarious.

The group of voters, and the elements described above, preceded Trump. He saw them, exploited them ruthlessly, and amplified them. For him, they should not just be skeptical of the GOP leadership and distrusting of the media, but they should resist the “rigged” system by voting for change—for Donald Trump. They should not just support a stricter immigration policy and a secure border, but they should abhor immigrants, see them as the cause of our problems, and see free trade and immigration as a conspiracy to impoverish and debase whites. They should not just be skeptical about President Obama’s place of birth and his legitimacy as president (as shameful as that skepticism is), and question his refusal to acknowledge the threat of Islamic terrorism, but they should see the truth before their eyes that Obama is working for our enemies to weaken the United States.

Trumpism will not dissolve after November 8 because the conditions that gave birth to it already existed. As such, we must affirmatively decide what the GOP will be in 2017 and beyond.

The Future of the GOP

After Trump secured the Republican nomination in May 2016, Republican leaders—no matter how critical of Trump they had been prior—began falling in line behind him. The party apparatus swung hard in his favor, denying attempts to reform the GOP, and put down an effort led by Mike Lee at the Republican National Convention to call for a roll call vote on new rules. The GOP threw in with Trump.

Most of the party’s leaders have supported Trump. Reince Priebus, Paul Ryan, Marco Rubio, John McCain, and Ted Cruz offered their support, and claimed that while they disagree with Trump on many things, they believe Hillary Clinton is a fundamental threat to the country and must be defeated. Often tacitly, but sometimes explicitly, they argued that Trump’s brand of racist, xenophobic, conspiratorial and authoritarian populism is preferable to Hillary Clinton sitting in the Oval Office.

Many in the party did so either out of fear that the contingent of voters described above would not vote for them if they did not back Trump, and so they could try to hold together the Republican coalition. They feared that without giving in to Trump, they, and the party, would be finished. They feared that group of voters—”the base.” Regardless of whether they believe the above to be true, they have, with their actions, threatened to make Trump president.

That is unacceptable.

Trump is fundamentally not conservative. Trump represents an active disdain toward limited government and individual rights, toward the rule of law, and toward an aspirational view of the United States. Trump’s implicit—and often explicit—appeals to white nationalism, and his attacks on non-whites, reject an America defined by a shared love of liberty and belief in the power of the individual and community. In its place, Trumpism substitutes a respect for “white” culture and history, where whites have given light to a world in perpetual darkness. Institutions are not to be trusted because they are rigged against whites. Instead, Trump—the champion of disaffected whites—should be trusted, and he should be trusted with extraordinary powers to make this country great again.

In the last few weeks, Trump has made much of the subtext explicit, and extended it. In a speech on October 13, Trump claimed that there is a “global power structure” that has conspired to rob the working class of wealth and jobs, and to end our sovereignty as a nation. Citing documents leaked by Wikileaks, Trump says that Hillary Clinton is a part of the conspiracy, and has plotted with international banks to plunder the nation and destroy our sovereignty, and is rigging the election with her co-conspirators in the media. What was once (crude) subtext in his slogan and statements is now just the text itself. Trump uses the words of a dictator: there is a conspiracy against the people, to impoverish them and disenfranchise them, and only a strongman like Trump can fight them.

The conservative vision of the United States—generally speaking—is we should dream big, and be free to work tirelessly to achieve those dreams. We should work together, voluntarily and within our communities, to help people in need and improve our communities. It is a view of the world where individual rights are sacred, and where respect for people—all people—is integral. It is a view of the world where our country is defined not by a shared ethnicity, but a thirst for liberty and self-determination. Our vision is not to be ruled by a strongman, or need the leadership of a great leader as president.

Fundamental to this view of the world is the rule of law. Without a set of laws that are comprehensible by all, and that are applied equally to all, there can be no limited government whose primary role is to protect individual rights, and provide space for a flourishing civil society. Without respect for our institutions, the rule of law will ultimately whither away.

Thus, Trumpism damages conservatism on two fronts. First, Trumpism challenges the idea that our nation is defined by ideas, and therefore challenges those ideas themselves. If our shared identity is not tied to a shared love for liberty, then what binds our nation together falls away. Doing so inherently breaks down the United States into its constituent ethnic, religious and cultural communities, and encourages people to fight for their communities to be empowered over others. If there is no shared identity, there is no reason to push for work to benefit everyone as a whole. Trump’s supporters offer a window into what that world looks like when they tell Hispanic Americans to “go home,” and when they threaten to intimidate non-white voters on election day, because for many of his supporters, being “American” is tied directly to ethnicity and culture. Second, Trumpism undermines faith in our institutions, and thus weakens the rule of law. If “the system”—the political parties, the government, the economy—are all “rigged” against us, why should the Constitution be seen as anything more than an old piece of paper? Why should we not support a strongman that will right the system, provide real Americans (whites) with jobs and dignity, and send the “foreigners” back to “their” country?

I admit that causation does not only flow in one direction; Trumpism is a response to a decline of faith in our institutions, caused by many of the reasons described earlier in this piece. However, while Trumpism is a response, it is also an amplifier, and a sharpening of distrust of our institutions into conspiracy theories. Trumpism is also not only a threat to conservatism, but a threat to our form of government, through the same mechanisms described above.

Our party’s leaders have tried to placate Trumpism’s supporters, to save their own jobs and to try to hold together the Republican coalition. But a coalition that includes people who seek to undermine the party’s and country’s values is not a coalition worth having.

Trumpism cannot be worked with, it cannot be directed toward productive ends, and it cannot be negotiated with. It must be called what it is: racist, xenophobic, authoritarian, anti-American. It must be fought, and it must not be accepted into the party. As conservatives, we cannot let Trumpism control the party. Our party leaders’ support for it is unacceptable.

Either the party will be pushed back toward working to solve our country’s problems with conservative ideas, or it will give in to the ethnic authoritarianism of Trump. There is no middle ground, and the party has made its choice.

Either the Republican Party stands for conservatism, and for respecting all Americans, or it stands for ethnic authoritarianism. If our party will not stand for conservatism, it is incumbent upon us to abandon the party, and start over. Today, the party has refused to abandon Trump after he called all illegal immigrants rapists, drug dealers and criminals; after he said John McCain is not a war hero; after he called for religious tests to be administered for immigrants, and a ban on all Muslims entering the country; after he repeatedly praised Vladimir Putin; after he repeatedly said he would compel the military to target wives and children of terrorists; after he sought out the support of white supremacists; after it became clear he has assaulted women; after Trump charged Clinton with being part of a global conspiracy to rob the working class and destroy the United States’ sovereignty; and after he insisted that our democratic system is rigged and illegitimate. The party has stood by him, and supports putting him—a demagogue that believes in nothing besides his own self-aggrandizement and the power of government—in the White House.

It is time for us to recognize the truth: the GOP is not a party worth saving, and not a party that anyone can support with their conscience intact.

I will not vote for leaders that did not repudiate Trump, and that did not repudiate Trumpism. I will not donate to them, I will not volunteer for them, and I will not offer them public support. It is time to support people who stood with dignity, people like Ben Sasse, Mike Lee, and Justin Amash, and to make room for new leaders that won’t bow to a vile authoritarian because of the letter next to his name and for fear of losing their position.

It is also our responsibility to help define what our new party does stand for after the election. Most importantly, the party must represent all Americans—Americans of all ages, cultures, ethnicities. Too often in the modern era, Republicans have given in to the idea that conservatism cannot appeal to non-whites, to the working class, and to the young. In 2012, we turned that idea into a campaign plank: Romney’s “47%” comment reflected the idea that conservative ideas fundamentally cannot appeal to a large part of the country, and thus that we should not even try. When Romney accepted Trump’s endorsement in 2012 (it is worth noting that the Romney campaign did not exactly enthusiastically embrace Trump’s endorsement, however—quite the opposite), and joked about President Obama’s birth certificate, he threw a bone to the group of voters that believe President Obama is not a “real” American. Romney certainly did not believe there is doubt about Obama’s fidelity to America, but giving those voters a knowing wink did not just “excite the base” a little ahead of the election—it legitimized racism in the party and in the country, and said that our party stands with them.

Those were shameful moments for Romney, a good man, but those ideas, and our leaders’ willingness to condone and encourage them, are part of the reason we now have Donald Trump as our nominee for president. That is both because we breathed life into those ideas and voters, and because that thinking is self-fulfilling: if we believe that non-whites, the working class and the young will never support conservatism, then that is reflected in our proposed policy, goals, focus and tone. If you all but tell non-whites that this party is not for you, why would they ever entertain the idea of supporting it? If you refuse to genuinely listen to other people’s experience living in America, what they care about, and what ideas they have, how can you expect them to take your ideas seriously? How can you expect that your proposals reflect the experiences and concerns they have?

The future of conservatism begins with something simple: listening. Listen to blacks, Hispanics, Asians, homosexuals, the middle class, the poor, the young. Listen, and try to understand what their experience in America is, what issues affect them, and what they believe.

Listening to other people and discussing with them will provide the grist for re-thinking what conservatism means in today’s world, and how we can address problems affecting all Americans. There already are many conservative thinkers doing precisely that. People like Reihan Salam, Yuval Levin, and Charles C. W. Cooke, have dealt seriously with the United States as it is in 2016. We need to do so as a movement.

No matter what specific policy you advocate for, starting with a respect and love for all Americans, and by genuinely listening to their experiences, is where our future begins.

A Danger to Our Political System

June 7th, 2016After defeating the British in the Revolutionary War, General George Washington almost certainly could have seized control, and made himself dictator. Washington was revered, the Continental Congress was weak, and the argument that the colonies needed the stable leadership of a tested leader in the post-war period would have been an easy one to make. But he did not.

Washington’s insistence on civilian control of the military is now a bedrock of the United States’ political system. The very thought of the military intervening in our country’s political decisions, much less overthrowing a democratically-elected Congress or president, sends a shiver down the spine of Americans, and would cut to the deepest level of what it means to be American. That idea—that elected civilians are our leaders, and the military answer to them—has held strong throughout our history.

There is no physical barrier, however, that prevents the military from intervening in the political process, or even from removing elected leaders from office. There is no wall, no defense. The military controls the weapons, and could do so if they pleased.

What has prevented it here is the norm created when Washington relinquished power to Congress. It hasn’t happened because it violates an idea of what is acceptable in our country, and one that defines our country.

That is not the only norm we depend on within our system. We have depended, too, on the idea that even if we wholly disagree with officials elected to office and want to see them unseated as soon as possible, they are afforded the respect of holding office. They were elected to office through our political system, and while we may think they should not be in office, we at least acknowledge they were elected. Similarly, elected leaders have respected a norm that they will not use their new powers to persecute the people they have replaced.

Together with the Constitution, which slows down and impedes the ability of majorities to enact sweeping changes to our laws, these norms (more numerous than the three discussed above) limit the scope of change possible for a single election. One general election year will not mean that the previous administration will be thrown in prison and minority groups’ freedom of speech will be denied. It will not mean that the economy will be nationalized. It will not mean that all members of a racial group will be rounded up and placed in internment camps.

By doing so, it turns down the temperature on our political debate. When people’s rights are not being directly decided by a single election, or whether the last administration will be imprisoned, there is much less incentive for people to make drastic decisions, like for a president to refuse to transfer power to the elected candidate. Such norms help ensure stability.

I fear we are well down the path of weakening the very norms that have girded our democracy.

I am, of course, writing about Donald J. Trump, who will be the Republican Party’s nominee for president.

Trump, though, did not start this erosion. We can trace it in its current form back at least to the 2000 election, and certainly to Obama’s presidency, with the right’s courting of birther conspiracy theorists that insisted President Obama is a foreigner and thus incapable of holding office. We can lay blame on President George W. Bush for expanding the scope of executive power, legitimizing torture, and on President Obama for enshrining Bush’s expansion of power and expanding it further still. There is much blame to go around.

Trump is something altogether new, however. Whereas the past two presidents have undermined our norms at the edges while still paying respect to them (the role of the executive in our system, respect for the rights of all Americans, and the legitimacy of our political system itself), Trump has undermined our system’s norms whenever he has found it politically advantageous to do so.

His commitment to the protections enshrined in U.S. constitution are questionable, at best, and if we assume the worst, downright frightening (the difficulty with Trump is that he’s not precise with words, so it’s sometimes hard to make sense of what he’s saying). He has expressed support for registering Muslims in a database, elaborating that they could “sign up at different places.” When a reporter asked how this was different from requiring Jews to register in Nazi Germany, Trump said “you tell me,” prompting The Atlantic’s David Graham to note that “it’s hard to remember a time when a supposedly mainstream candidate had no interest in differentiating ideas he’s endorsed from those of the Nazis.” Trump, for good measure, has also refused to disavow President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s internment of Japanese-Americans.

That is not even close to an exhaustive list, and Trump has added to it since, by stating that Gonzalo Curiel, a federal judge presiding over a lawsuit he is involved in, should Curiel should recuse himself from the case for impartiality because Curiel is of Mexican descent.

By doing so, Trump is using his position as a candidate for president to threaten a sitting judge, and is undermining the legitimacy of the judiciary. When a candidate for president uses his position to question a judge’s impartiality, the judiciary’s stature is weakened. What good are court rulings if the president states rulings that run counter to their interests are biased and illegitimate? Through his statements, Trump lessens the standing of the judiciary, and raises the specter of ignoring rulings altogether if he is elected. After all, why should the president respect “biased” and illegitimate rulings from an unelected body of judges?

Trump, too, is fond of threatening people he finds disagreeable. He has threatened the Ricketts family and David French’s family with consequences if they do not fall in line, and has used lawsuits as a bludgeon against people in the past. Those threats appear to be part of who Trump is and what he believes a good leader to be. He is, after all, the man that complimented the Chinese Communist Party’s strength for putting down the 1989 Tiananmen democracy protest with tanks and bullets, and the man that said he would compel the U.S. military to carry out unlawful orders, even if they refused.

Is that our norm of what the executive—the body of government that signs and enforces laws drafted by the democratically-elected legislature—is? Someone that questions the impartiality of a federal judge because of the judge, and uses his race as an excuse? Someone that doesn’t recoil at the idea of placing American citizens of one religion in a database so they can be tracked by the federal government? Someone that finds murdering the wives and children of terrorists as an intentional strategy morally acceptable, and believes it is “leadership” to force the military to carry out such atrocities? Someone that thinks it is not beneath a president to threaten private citizens for crossing him?

Those are not the norms we have established, or the norms that have provided remarkable stability in our political system since our founding. They are the signs of someone that fancies himself an authoritarian, and of a person that believes anything, or anyone, that stands in his way are to be crushed. They are the marks of a demagogue willing to do anything in the pursuit of power.

Trump will likely not be elected president. Despite that, by allowing this man to be the nominee for president for the Republican party, by allowing him to say and do the things he does, we are doing damage to our system of government. We are normalizing Trump’s behavior, normalizing his blatant use of racism and threats. He is raising the specter that things we did not think people would ever do, could be done as a result of a single election.

Trump will not be the end of our system, even if elected. But he is accelerating the decline of what has helped make our form of government so strong and resilient. And for that, we—members of the party that has elevated this man to be our nominee—should be deeply ashamed.

There is no honor in sticking by a party that makes Trump our standard bearer, no good to come from party unity.

Trump

February 29th, 2016The United States is a country founded on ideas. Ethnicity and religion are not what have bonded us from our founding. It is the fundamental ideas expressed in our Declaration of Independence, and in our fight for independence, that run through our country’s history. Our founding set forth that individuals are ends unto themselves, and deserve to be respected as such; that government’s role is not to be the ultimate source of authority and power within society, but merely to protect the people’s pre-existing rights; and that through our will and determination, there is no limit to what we can accomplish.

We have not always honored and lived up to those ideas. Our founding itself was stained with the deepest of shames, the enslavement of human beings, while our founders argued for the dawn of a new beginning. We subjugated the Indians, and cruelly abused them like non-humans. We let the cancer of slavery metastasize, until war was the only option remaining; and after slavery was broken, we allowed Jim Crow to replace it. We have not yet entirely grappled with what our country’s greatest shame means, nor have we left the effects of slavery to the pages of history. They remain here with us today.

And yet America is a tremendous miracle. From British colonialism and abuse, we won our independence as a country, and forged one of the greatest works of humanity: the Constitution. The Constitution not only explicitly laid out the extent of the federal government’s powers, and enumerated the rights of the people that must not be infringed, but created a political system that, through separation of powers and the pitting of different power centers against each other, limited the ability of the government to fall under dominance of a single group and single passion of the time, to limit the ability of the government to be used as a tool of repression, even if it represented the will of the majority. It is a marvel of all time.

Through our unique genesis, we forged an identity separate from ethnicity and religion. Our identity, what it is to be American, centers around our belief in respect for each other as individuals, and for our right to pursue our dreams. By doing so, our country has been able to adopt waves of immigrants, people utterly different from the people already here, and integrate them into our nation. Whatever our race, religion and culture, if we share the same fundamental ideas, we are one people. Our identity is our ideas.

We have not always lived up to that, either. But it is remarkable how many different peoples have immigrated to the United States since our founding, and in the ensuing decades became as “American” as anyone else. That is the strength of our country: We will take anyone, if they believe there is a better tomorrow through work. We can all have different skin colors, follow a different religion (or none at all), eat different food, have differing ideas for what the good life is, even speak different languages—and be unified as a single people. That is a miracle, and despite not always living up to it, it also aptly captures something fundamental to our country.

Our country, at its best, is not about “staying with our own kind,” or taking from others to increase the lot of “our people.” Our country is about being different, having different ideas—but being on the whole unified under an assumption that we can create a better tomorrow for everyone through work.

That is also why I have found Donald Trump’s campaign for president so disturbing. Trump has built his campaign—to “make America great again”—on the belief that America is lost, that we are an embarrassment, that we are weak, and that we can only return to “greatness” on the back of a great leader. Trump has made his appeal not by arguing for how we can empower all of us, as Americans, to pursue our dreams for a better tomorrow, but by appealing to the ethnic and religious differences between Americans. He has not just argued that open immigration could be harmful and we should be cognizant of it, but that Mexicans are rapists, drug dealers and killers. He has not just pushed for being mindful of the threat posed by Islamic terrorism, but has flirted with the idea of registering all Muslim Americans in a database so they can be tracked, and with barring Muslim Americans traveling abroad from returning to their own country. He is a man that has played on conspiracy theory and overt racism.

Trump has praised the “strength” of repressive dictators such as Vladimir Putin and repressive governments such as the People’s Republic of China, and has said—often on the same day he threatened an individual or company with consequences if he is elected—that he would open up libel laws so journalists could be sued for writing or saying what he finds to be misleading or false.

Trump claims he is conservative. What I see is a man that, in order to rise to the top, willfully pulls on the ethnic and religious differences in our country, and uses and amplifies prejudice and hatred, to garner the support of whites. He is intentionally dividing us as a nation, pitting white Christians against Hispanics and Muslims, regular people against the wealthy and “media elite,” “Americans” (by which he means white people) against foreigners, which includes not only foreign nations, but American citizens that have descended from immigrants of foreign nations. Trump is tearing at the very fabric of our nation.

He tears at it, while also undermining the bedrock idea that the government does not lead our nation, but that the individuals do. Ideology may not be fundamental to Trump, but a belief in the supremacy of great leaders, and in their necessity for a country to do great things, is. That belief underlies his fondness for Putin, a man unafraid of using the power of the state toward his ends, and to crush his opposition. It underlies his praise for the PRC in 1989, when the PRC crushed a budding protest movement in Tiananmen Square in Beijing. And it underlies his support for the use of torture and for killing the families of terrorists—great leaders do what is necessary to win.

Trump, then, is a man willing to divide us as a people, so that he can lead us to “greatness.” Trump’s idea of leadership is not to respect the limits of the federal government’s power, and the presidency’s power, but to do whatever he thinks is necessary (laws, morals, and individual rights be damned) to show our strength and impose his will, both on the world and at home. Trump does not see himself as the leader of a country defined by its rights, but as someone smarter and stronger than everyone else, and thus entitled to impose his will on whomever he pleases. There is a reason that “little,” “loser,” “low-energy,” and “weak” are some of his most-used insults for his opponents, and he speaks so often of being a “winner.”

I cannot support Trump because he is fundamentally destructive of what our country is. Trump is willfully tearing at what holds our country together and what defines us as a people. I cannot, and will not, support a man that appeals to our fears, to our baser instincts, that turns every issue into one of us versus them, and that peddles in conspiracy and racism. I cannot, and will not, support a man that fancies himself an authoritarian, a man that threatens people that say things he doesn’t like, and threatens to undermine the first amendment. I cannot, and I will not.

I will not support Donald Trump if he is the Republican Party’s nominee for president. If the GOP is remade in his image, I will leave the party. I owe the party no obligation, if the party has become destructive of what I cherish most. I cannot, and I will not.

I promise that I will fight Trump, the demagogue, now, and if he wins the nomination. I will not accept it, and nor should you.

If, like me, you are a Republican, I appeal to you to vote in your state’s primary, and to vote against Donald Trump. He has not won yet, and we can still fight. Let us defeat him. Let us win a victory for what we love about our country.

“Free” electric vehicle chargers are an excellent example of what happens when valuable resources are priced at zero:

The bad moods stem from the challenges drivers face finding recharging spots for their battery-powered cars. Unlike gas stations, charging stations are not yet in great supply, and that has led to sharp-elbowed competition. Electric-vehicle owners are unplugging one another’s cars, trading insults, and creating black markets and side deals to trade spots in corporate parking lots. The too-few-outlets problem is a familiar one in crowded cafes and airports, where people want to charge their phones or laptops. But the need can be more acute with cars — will their owners have enough juice to make it home? — and manners often go out the window.

There is always a cost, and the resource is always allocated in some manner. But it is usually in a much more arbitrary, inefficient, and unjust manner.

October 12th, 2015Jonathan Blanks writes on why he owns guns and believes gun ownership is everyone’s right:

Like many Americans, my family history is closely tied to firearms. I was raised with a sense of duty to protect my loved ones. Danger wasn’t something that was abstract or imaginary in my family history or my upbringing, and so we had to learn to deal with it.

I’m not a Second Amendment absolutist, and I am open to changes to our gun laws. But gun ownership is important to me, and responsible individuals must be allowed to make the choice for themselves and their families if they want to own firearms.

Absolutely worth reading, especially with Twitter full of righteous stupidity like this:

So if you define “liberty” as the right to own a gun, go fuck yourself. You are a disgrace to all that’s good and right about America. – Mike Monteiro

Monteiro’s indignant tirade is representative of a sentiment that, in typical fashion, swept across Twitter and fell away in a matter of days—all anger, hate and righteous assurance that the speaker is absolutely right, and that the people they disagree with are not only wrong, but utterly stupid or evil. But for all of this righteousness, all of this anger, it is all hot air.

This sort of thing replaces thinking about an issue, reading about it and reading what other people think and actually considering it, with posturing. It is, ultimately, self-aggrandizing. It accomplishes zero, besides make the person feel good about themselves for their 140 characters.

On the opposite end of the spectrum is Jonathan Blank’s piece. He doesn’t argue by denigrating people he disagrees with, or questioning their intelligence or motivations—he makes a calm, reasoned argument for what he thinks.

Blanks argues that, as a black family in Indiana, guns were vital to his family’s defense from the KKK, and that having a gun was necessary to defend his girlfriend’s friend from an abusive husband. His thesis is that people have the right to protect themselves, and a gun is often the only way to do that.

That doesn’t just extend to defending yourself against other individuals, but also against an abusive state. The left is fond of arguing that gun ownership as a check against government violating our liberty is absurd because no one with a shotgun or AR-15 could successfully take on the U.S. military. This argument is absurd. The goal is not simply to defeat an abusive government, but to make it prohibitively difficult and bloody for the government to become tyrannical. And, indeed, it would certainly be possible to defeat an abusive government—the Afghan wars, Iraq war, Vietnam war,… and on and on show what guerrilla fighters can do against an overwhelmingly superior force.

But Blanks makes an even more important point: even if defeat was certain, it would not matter. Individuals have the right to defend themselves against violations of their rights, whether it comes from individuals or the government, and whether or not they will win. And guns are vital to that. There is no liberty if people cannot even attempt to protect themselves.

October 12th, 2015

My thanks to Transpose for sponsoring this week’s RSS feed.

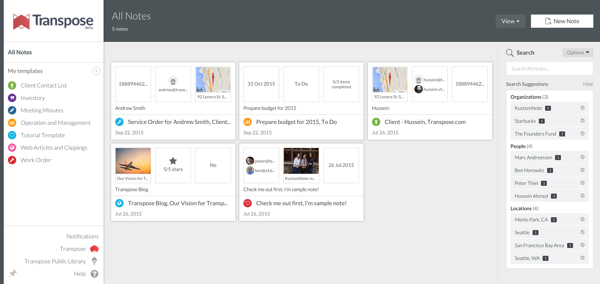

Transpose is a dead-simple way for anyone to build databases for their data. Anyone can use Transpose, in any field, because of how it works: Transpose lets you create simple forms for collecting your data, and from there, you can filter, sort and search your data in any way you want. Even better, Transpose identifies names and locations to create suggested searches, so you can quickly drill down in your data for what you are looking for. If you are creating a database of media contacts for your new project, or even organizing purchase orders for your business, don’t use a spreadsheet: Transpose is the right tool for the job. You can create a form that is exactly right for your task. Transpose is tailor-made for these sorts of tasks, so you can quickly enter your data, sort through it, and even export in a variety of formats. And, of course, this is all online, and not stuck in a spreadsheet on your PC. Transpose is a single place you can do data management, note-taking and to-do tracking all in a single, integrated place, and replace disparate tools like Evernote and Trello with a single tool.

Use the right tool for the job. Give Transpose a try today.

Sponsorship by the Syndicate.

September 29th, 2015iOS 9 and the Information Ecosystem

June 25th, 2015Earlier this month, Apple introduced iOS 9 with new search and Siri features. In iOS 9, users will be able to search for both specific activities and content that is contained in iOS applications. What this means is that users should be able to search for “sunburn” to find information on how to treat sunburns that is provided by iOS medical applications, and tapping the item will immediately launch it in the application. Additionally, these features will allow users to reference whatever they are looking at in a reminder they create through Siri. That is, when looking at an Amazon product page, users will be able to tell Siri “Remind me to buy this tonight,” and Siri will add a reminder with the link included.

Prior to iOS 8, an application’s functionality and content were indivisible from the application itself. If a user was looking at a photo in their photo library and wanted to edit it using a more powerful editing application they had installed, they had to leave Photos, open the editing application, and find and open the photo again there. If the user needed to access a text document they had stored in Pages, they had to launch Pages. In iOS 8, Apple eliminated the redundancy in the former example through extensions, which allow developers to atomize their application’s functionality and allow users to utilize it outside the scope of the application itself.1

The latter example is still true within iOS 8. Content is indivisible from the application itself. iOS 9, however, begins to break content and tasks from the application by making them searchable through what used to be called Spotlight on iOS but is now just Search.

The features around Search and Siri Reminders are absolutely useful. It is flexible and convenient to be able to move over to the resurrected Search page on the home screen and type in, say, “Denver” to find my flight or Airbnb reservation. What I find more interesting than the user-facing features here, though, are the tools provided to developers to make this possible, and the direction task and content search indicate iOS may be heading.

An Information Ecosystem

To allow iOS’s new Search feature to surface tasks and content that are contained within applications, developers must indicate to the system what within their application is content that should be surfaced, and what type of content it is (image, audio, event, etc). Developers do much the same thing for tasks. Somewhat similarly, extensions indicate to the system what kind of content they can consume.

This is referred to as “deep linking,” because it allows users to follow a “link” to somewhere deep within an application for some kind of task or content, exactly like clicking on a link in Google to a news article within a website, as opposed to going to the website’s home page and moving through their hierarchy to the article. “Deep linking,” while apt, is also somewhat misleading because this allows much more than just search. When developers update their applications to take advantage of Apple’s new APIs for identifying content and tasks to the system, they will be helping the system structure what–and what kind–of data is on the user’s device. The system will know what content is on a user’s device, what kind of content that is, and what kind of content applications provide. The system will know what photos, contacts, events (say, hotel reservations), and music are on a user’s device.

Using these tools, we could begin to construct an understanding of what the user is doing. Applications are indicating to the system what tasks the user is doing (editing a text document, browsing a web page, reading a book), as well as what kind of content it is they are interacting with. From this, we can make inferences about what the user’s intent is. If the user is reading a movie review in the New York Times application, they may want to see show times for that movie at a local theater. If the user is a student writing an essay about the Ming dynasty in China, they may want access to books they have read on the topic, or other directly relevant sources (and you can imagine such a tool being even more granular than being related to “the Ming dynasty”). Apple is clearly moving in this direction in iOS 9 through what it is calling “Proactive,” which notifies you when it is time to leave for an appointment, but there is the possibility of doing much more, and doing it across all applications on iOS.

Additionally, extensions could be the embryonic stage of application functions broken out from the application and user interface shell, one-purpose utilities that can take in some kind of content, transform it, and provide something else. A Yelp “extension” (herein I will call them “utilities” to distinguish between what an extension currently is and what I believe it could evolve into) could, for example, take in a location and food keywords, and provide back highly rated restaurants associated with the food keywords. A Fandango extension could similarly provide movie show times, or even allow the purchase of movie tickets. A Wikipedia extension could provide background information on any subject. And on and on.

In a remarkable piece titled Magic Ink, Bret Victor describes what he calls the “Information Ecosystem.” Victor describes a platform where applications (what he calls “views”) indicate to the system some topic of interest from the user, and utilities (what he calls “translators”) take in some kind of content and transform it into something else. What this platform would do is then provide inputs to all applications and translators. The platform would provide some topic of interest that has been inferred from the user; as I described above, this may be a text document where the user is writing about the Ming dynasty, or a movie review the user is reading through a web browser. Applications and translators can then consume these topics of interest and information provided by utilities. The Fandango utility I describe above could consume the movie review’s keywords, for example, and provide back to the platform movie show times in the area. The Wikipedia utility could consume the text document, and provide back information on the Ming dynasty.

What is important here is that the user intent that can be inferred from what the user is doing and what specific content they are working with, and the utilities described above, could be chained together and utilized by separate applications for the user, in such a way that was not explicitly designed beforehand. Continuing the movie review case, while the user is reading a review for Inside Out in the New York Times application, they could invoke Fandango to find local show times and purchase tickets. This could occur either by opening the Fandango application, which would immediately display the relevant show times, or through Siri (“When is this playing?”). More interesting, one could imagine a new kind of topical research application that, upon notice that the user is writing an essay related to the Ming dynasty, pulls up any number of relevant sources, from Wikipedia (using the Wikipedia utility) and online sources (papers, websites). Perhaps the user has read several books about the Ming dynasty within iBooks, and has highlighted them and added notes. If iBooks identifies that information to the system, such a research application could even bring up not just the books, but specific sections relevant to what they are writing, and passages they highlighted or left notes on. Through the platform Victor describes, the research application could do so without being explicitly designed to interface with iBooks. As a result, the work the user has done in one application can flow into another application in a new form and for a new purpose.

To further illustrate what this may allow, I am going to stretch the above research application example. Imagine that a student is writing an essay on global warming in Pages on the iPad in the left split-view, and has the research application open on the right. As the user is writing, the text will be fed into a topic processor, and “global warming” will be identified as a topic of interest by iOS. Because earlier that week they had added a number of useful articles and papers to Instapaper from Safari, Instapaper will see “global warming” as a topic of interest, and serve up to the system all articles and papers related to the topic. Then, a science data utility the user had installed at the beginning of the semester would also take in “global warming” as a topic, and would offer data on the change in global temperature since the Industrial Revolution. The research application, open on the right side of the screen, will see the articles and papers brought forward by Instapaper and the temperature data provided by the science data utility, and make them immediately available. The application could group the papers and articles together as appropriate, and show some kind of preview of the temperature data, which could then be opened into a charting application (say, Numbers) to create a chart of the rise in temperatures to put in the essay. And the research application could adjust what it provides as the user writes, without them doing anything at all.

What we would have is the ability to do research in disparate applications, and have a third application organize our research for the user in a relevant manner. Incredibly, that application could also provide access to relevant historical data for the user as well. All of this would be done without the need for this application to build in the ability to search the web and academic papers for certain topics (although it could, of course). Rather, the application is free to focus on organizing research in a meaningful and useful way in response to what the user is doing, and they would just need to do so by designing for content types, not very specific data formats coming from very specific sources.

Utilities, too, would not necessarily need to be installed with a traditional application, or “installed” at all. Because they are face-less functions, they could be listed and installed separate from applications themselves, and Apple could integrate certain utilities into the operating system to provide system-wide functionality without any work on the user’s part. For example, utilities could be used in the same way that Apple currently integrates Fandango for movie times and Yelp for restaurant data and reviews. Siri would obviously be a beneficiary of this, but all applications could be smarter and more powerful as a result.

A Direction

Apple hasn’t built the Information Ecosystem in iOS 9. While iOS 9′s new search APIs allow developers to identify what type of content something is, we do not yet have more sophisticated types (like book notes and highlights), nor a system for declaring new types in a general way that all applications can see (like a “movie show times” type).2 Such a system will be integral to realizing what Victor describes, and is by no means a trivial problem. But the component parts are increasingly coming into existence. I don’t know if that is the direction Apple is heading, but it certainly *could be*, based on the last few years of iOS releases. What is clear, though, is Apple is intent on trying to infer more about what the user is doing and their intent, and provide useful features using it. iOS 7 began passively remembering frequently-visited locations and indicated how long it would take to get to, say, the user’s office in the morning. iOS 9 builds on that sort of concept by notifying the user when they need to leave for an appointment to get there on time, and by automatically starting a certain playlist the user likes when they get in the car. Small steps, but the direction of those steps is obvious.

I hope Apple is putting the blocks in place to build something like the Information Ecosystem. Building the Information Ecosystem would go a long way to expanding the power of computing by breaking applications–discrete and indivisible units of data and function–into their component parts, freeing that data to flow into other parts of the system and to capture user intent, and for the functionality to augment other areas in unexpected ways.

I believe that the Information Ecosystem ought to be the future of computing. I hope Apple is putting the blocks in place to build something like it.

- Although for the photos example, Apple hasn’t totally finished the job; while you can use photo editing extensions from within the Photos application, you can’t do so for photos added to emails or iMessages. [↩]

- We can declare new types, and other applications can use them, but as far as I know each developer must be aware of those types separately, and build them into the application. This makes it difficult to use data types declared by third-parties. [↩]

Today is an excellent day to re-read Ken White’s excellent overview of the Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr’s oft-referenced “shouting fire in a theater” quote:

January 7th, 2015Holmes’ quote is the most famous and pervasive lazy cheat in American dialogue about free speech.

During a Reddit AMA earlier this week, Elon Musk said he hopes to announce his Mars transport system plans.

As you’d expect, I’m incredibly excited about this. We are still obviously a long ways away from the first manned mission to Mars, but there is finally substantive work being done to get us there. Of course, NASA announced late last year that the Orion space capsule is a part of their plan toward a manned mission to Mars, which is terribly exciting. Humans conducting experiments on Mars and exploring the planet is something I hope to see before I die.

But Musk and SpaceX, I think, are even more exciting, because Musk’s intent is not just to send a scientific mission to the planet. Musk’s intent is to send waves of one-way missions to Mars full of people to colonize the planet. Musk’s intent, then, is a magnitude more ambitious than NASA’s. Musk’s intent is to start humanity’s expansion through space.

In October, I lamented our lack of progress with space travel. I hope more than anything that, in two decades, I can look back at that piece and laugh—while watching the greatest explorers in the history of our species make one more giant leap for humanity.

January 7th, 2015A Jovian Dream

October 1st, 2014Jupiter beckons in the distance, a small light, the greatest planet of all

I stare through the window, timeless, as the light slowly grows larger

I wonder what it will be like to see it with my own eyes

Swirls of orange and red and brown, a globe so large I can’t comprehend

The Jovian moons circling around the greatest planet of all, enraptured,

Captured

It is growing larger through the window

Through the window that separates me from the void,

Separates warmth and air and life from emptiness and death

This is what we have constructed

To ferry us across the great emptiness of space

It is larger still, I see color!

To see it with our own eyes

I see the moons!

To see if there is life beyond our little blue dot, so far away

To strike off into the unknown once again

To extend humanity beyond our home

I see it, I see it! I see!

But oh, this is the dream of a child

A great dream, but a dream

Remembered by an old man,

What could have been

After China placed limitations on candidates for Hong Kong’s city leader, Hong Kong erupted in protest. This, of course, presents a large challenge to Xi Jinping and the PRC. Edward Wong and Chris Buckley write for the Times:

China’s Communist Party has ample experience extinguishing unrest. For years it has used a deft mix of censorship, arrests, armed force and, increasingly, money, to repress or soften calls for political change.

But as he faces massive street demonstrations in Hong Kong pressing for more democracy in the territory, the toolbox of President Xi Jinping of China appears remarkably empty.

It’s an especially difficult challenge for Beijing because their options are so limited. If they come to an agreement with the protesters, or even remove the limits entirely, it will not only show weakness on Beijing’s part (something they are loathe to do), but could encourage similar protests in China proper. But they also have little ability to clamp down on protests in Hong Kong.

This is as large a threat to the PRC we’ve seen in years, and it has the potential to rival the 1989 protests.

September 29th, 2014Apple Watch

September 15th, 2014The phone dominates your attention. For nearly every use, the phone has your undivided attention. Browsing the web, Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat, watching video, reading, messaging—all require focus on a screen that fills your vision, your primary attention, and generally some kind of interaction. Everything else, too, is always a home button or notification-tap away at all times.

Is that a shock when the phone is the single gateway to nearly everything? The PC is now for doing work, but the phone is for messaging, taking photos, sharing them, the web, Twitter, Facebook, finding places to go, getting directions there, and even making calls.

That is the reason we find ourselves, when we receive a message and pull out our phones to respond, often descending into a muscle memory check of our other iMessages, emails and Twitter stream. We pull out our phone for one purpose, like responding to a message or checking our schedule, and end up spending several mindless minutes (or, if I am honest, more than “several minutes”) checking in on whatever it is. We find ourselves doing this even when we shouldn’t. We do it while seeing friends and family, while out to dinner with them, while at home with family when we should be spending time with them or doing other things.

I used “we” above because I think anyone with a smartphone, or anyone who knows people with them, can find truth in it to a greater or lesser extent.

My concern with wrist-worn “smartwatches,” starting with the Pebble, is that they appear to primarily exist to push notifications that we receive on our phone to our wrist. They seem to exist to make dealing with phone calls, messages, updates easier; seeing them, ignoring them, replying to them. They are there to make dealing with our phones more convenient. And in large part, that is how smartwatches have been designed and used. “It’s there so I don’t have to pull my phone out of my pocket.”

But that idea of what smartwatches are for, making it more convenient to deal with the flood of notifications and information our phones provide us, is unimaginative. I think what the smartwatch can do is make the phone unnecessary for many purposes, create new purposes altogether, and allow us to benefit from a wrist-sized screen’s limitations.

The Apple Watch

On September 9th, Apple introduced their long-awaited watch, appropriately named the Apple Watch (from herein “the Watch”). We won’t be able to fully understand what Apple’s built until next year, but they did provide a fairly detailed look at the Watch and the software it runs.

It appears that, in contrast to Google’s approach with Google Wear (which is heavily focused on showing single bits of information or points of interaction on the screen, and relies on swiping between cards of data and interaction), Apple intends the Watch to run fairly sophisticated applications. The Watch retains the iPhone’s touch interface, but Apple has designed new means of interaction specific to a small screen. In addition to the tap, the Watch brings the “force tap,” which is used to bring up different options within applications (like, say, the shuffle and AirPlay buttons within the music application), and the “digital crown,” a repurposing of the normal watch’s crown into a sort of scroll wheel for the Watch. Using the digital crown, users can zoom in and out of maps and scroll through lists with precision and without covering the small screen. And, most interestingly, they have replaced the familiar vibration alert in our phones with a light “tap” from the Watch to notify the user.

What this allows is fairly sophisticated applications. You can not only search for locations around you, but you can zoom in and out of maps. You can scroll through your emails, messages, events or music. You can control your Apple TV.

This subsumes many of the reasons we pull out our phones during the day. We can check our schedule for the day, check a message when it’s received and send a quick reply, find a place to get a drink after dinner (and get directions there without having to walk and stare at your phone), ignore a phone call by placing your hand over your wrist, or put something on the Apple TV.

But what force taps and the digital crown will not do is make the Watch’s small screen as large as a phone’s. You can’t type out a reply to a message or email. You can’t browse the web for something. You can’t dig through a few months of your email to find a certain one. You can’t mindlessly swipe through Twitter (well, you could, but it’s going to be pretty difficult). That, though, is an advantage the Watch has over the phone. Because it is inherently limited, it also has to be laser-focused on a single purpose, and while using it, you are limited to accomplishing something. It’s a lot harder to lose yourself in a 1.5″ screen than it is in a 4+ inch screen.

That’s going to be one of the Watch’s primary purposes for existing: allowing us to do many of the things we do on our phones right now, but in a way that’s limited and, thus, less distracting. If you’re out to dinner and receive a message (and haven’t turned on Do Not Disturb), you’re going to be a lot less likely to spend a couple minutes on a reply, and then Instagram, if you’re checking and responding it to it on the Watch. It just doesn’t work that way.

In that way, I think Apple has embraced the wrist-worn watch’s inherent limitations. Rather than try to work around them, they are using them. They’ve built new means of interaction (force tap, digital crown, “taptic” feedback) that allows fairly sophisticated applications, but they didn’t use them to cram iOS in its entirety into the Watch.

What I think Apple is trying to do is build a new mode of personal computing on the wrist that is molded from the inherent limitations and opportunities that creates.

Truly Personal

In Jony Ive’s introduction to the Watch, Ive ends with a statement of purpose of sorts for it. He says,

I think we are now at a compelling beginning, actually designing technology to be worn. To be truly personal.

That sounds like a platitude, but I think it defines what Apple is trying to do. “Taptic feedback,” which Dave Hamilton describes as feeling like someone tapping you on the wrist, is a much less intrusive and jolting way of getting a notification than a vibration against your leg or the terrible noise it makes on a table, and more generally, focusing the Watch’s use on quick single purposes is, too.

What is interesting to me, though, is they are using the Watch’s nature to do things in a more personal—human—way, and to do things that the phone can’t. When providing directions, the Watch shows them on the screen just as you would expect on a phone, but it also does something neat: when it’s time to turn, it will let you know using its Taptic feedback, and it differentiates between left and right. As a result, there isn’t a need to stare at your phone while walking somewhere and getting directions.

They’ve also created a new kind of messaging. Traditionally, “messages” are either words sent from one person to another using text or speech. Since messages are communication through word, something inherently mental or intellectual rather than emotional, they are divorced from emotion. We can try to communicate emotion through text or speech (emoticons serve exactly that purpose), but communicating emotion to another person is always translated into text or speech, and then thought about by them, rather than felt. In person, we can communicate emotion with our facial expressions, body gestures, and through touch. There’s a reason hugging your partner before they leave on a long trip is so much more powerful than a text message saying you’ll miss them.

In a small way, using the Watch, Apple is trying to create a new way to communicate that can capture some of that emotion. Because the Watch can effectively “tap” your wrist, others can tap out a pattern on their Watch, and it will re-create those taps on your wrist, almost like they are tapping you themselves. You could send a tap-tap to your partner’s wrist while they are away on a trip just to say that you’re thinking about them. Isn’t that so much more meaningful a way to say it than a text message saying it? Doesn’t it carry more emotion and resonance?

That’s what they mean by making technology more personal. It means making it more human.

The Watch is not about making it more convenient to deal with notifications and information sent to us. It’s not even about, as I described above, keeping your phone in your pocket more often (although that will be a result). The Watch is creating a new kind of computing of our wrists that will be for different purposes than what the phone is for and what the tablet and PC are for. The Watch is for quickly checking and responding to messages, checking your schedule, finding somewhere to go and getting directions there, for helping you lead a more active (healthier) life, and for a more meaningful form of communication. And it will do that without sucking our complete attention onto it, like the phone, tablet and PC do.

The Watch is for doing things with the world and people around us. Finding places to go, getting there, exercising, checking in at the airport, and sending more meaningful messages. Even notifying you of a new message (if you don’t have Do Not Disturb turned on) while out to dinner with family or friends serves this purpose, because if you have to see it, you can do so in a less disruptive way and get back to what you are doing—spending time with people important to you.

The Watch is a new kind of computing born of, and made better by, it’s limitations. And I can’t wait.

The founders of Siri are working on a new service called Viv that can link disparate sources of information together to answer questions:

But Kittlaus points out that all of these services are strictly limited. Cheyer elaborates: “Google Now has a huge knowledge graph—you can ask questions like ‘Where was Abraham Lincoln born?’ And it can name the city. You can also say, ‘What is the population?’ of a city and it’ll bring up a chart and answer. But you cannot say, ‘What is the population of the city where Abraham Lincoln was born?’” The system may have the data for both these components, but it has no ability to put them together, either to answer a query or to make a smart suggestion. Like Siri, it can’t do anything that coders haven’t explicitly programmed it to do.

Viv breaks through those constraints by generating its own code on the fly, no programmers required. Take a complicated command like “Give me a flight to Dallas with a seat that Shaq could fit in.” Viv will parse the sentence and then it will perform its best trick: automatically generating a quick, efficient program to link third-party sources of information together—say, Kayak, SeatGuru, and the NBA media guide—so it can identify available flights with lots of legroom. And it can do all of this in a fraction of a second.

If I understand the advancement they’ve made, the service (1) will allow third-parties to link in their information or service and define what it is in a structured fashion (so Yelp could define their information set as points of interest, user ratings and reviews, and Uber could make their car service available) and (2) the service knows how to connect multiple information and/or services together so that it can answer a user’s question or fulfill their request.

The Wired article linked above provides an example of what this would look like. A user tell Viv that they need to pick up a bottle of wine that pairs well with lasagna on the way to their brother’s house.

Providing a solution to that requires the interaction of many different information sets and services. Viv would (1) use the user’s contacts to look up their brother’s address, (2) use a mapping service to create a route from the user’s current location to their brother’s house, along with some radius along the route with which the user is willing to deviate from to pick up the bottle of wine, (3) identify what ingredients compose “lasagna,” (4) identify what wines pair well with those ingredients, and (5) find stores within the specified radius of the user’s route that carries that wine.

That’s incredibly complicated. If Viv can do that not just for pre-planned scenarios (like Siri and Google Now currently do), but for arbitrary scenarios provided they have the necessary information and services, then they must also have made an advancement in natural language recognition to support it.

What most intrigues me, though, is the founders’ vision for providing Viv as a “utility” akin to electricity, so that any device could tap into the service and use its power. Effectively, what they are trying to build is a structured, universal data source. I wrote about this idea when Apple released Siri in 2012 and it’s something I’ve been thinking about for the last 5 years. The idea is to structure the world’s data so that it can be retrieved in a useful (read: computer usable) form.

It’s incredibly ambitious. With a sophisticated natural language front-end, users could ask for information on virtually anything and receive it immediately. You could, while cooking (is it obvious I make an application for cooking?), ask for healthy substitutes for butter, or the proper technique for blanching vegetables. The service would also have an API so that other software and services could access it. Imagine a hypothetical research application that allows you to request (not search!) the average temperature for each year in Los Angeles for 1900-2010, and getting back the data, and the data assembled into a chart. And then imagine requesting the average temperature for Los Angeles for 1900-2010 along with the amount of CO2 emissions for each year in the same range. With the data charted.

That’s a rather mundane example, actually. Imagine what kind of analyses would be possible if the world’s data is not only made available, but is immediately available in a structured format, and is constantly updated as the data is produced. There is the potential here, I think, for this to be as important as the advent of the Internet itself.

What concerns me, though, is how will this be made accessible. The article quotes Dag Kittlaus as saying that they envision deriving revenue from referrals made within the service. So, if you buy something through Amazon or request an Uber ride through Viv, they will earn a referral fee for it.

That makes perfect sense and is fairly brilliant. But what about making scientific data accessible? Will that require some kind of payment to access? Will I only be able to access that information through some kind of front-end, like a research application that I’ve paid for (and where the application’s developers pay some kind of fee to get access)? That would certainly be an advancement over where we are today in terms of making data accessible, but it would also prevent incredible innovation that open access could allow. Imagine if Wikipedia was a for-profit operation and, instead of being publicly available, was only accessible through subscription or through some kind of front-end. It would not be nearly the same thing.

It is heartening, though, that they are thinking so deeply about a business model. It would be a shame if such a terrific idea and incredible technology fails (or is absorbed by another company) because they hadn’t considered it. However, I hope they are considering, too, what open access to certain kinds of data (historical, political, scientific) could allow.

August 12th, 2014I Want to Know

August 8th, 2014When I was growing up, I was fascinated by space. One of my earliest memories—and I know this is strange—is, when I was four or five years old, trying to grasp the concept of emptiness in space. I imagined the vast emptiness of space between galaxies, nothing but emptiness. I tried to imagine what that meant, but most of all, I tried to imagine what it would look like.

That question, what color empty space would be, rolled around my brain the most. I couldn’t shake it. I would be doing something–playing Nintendo, coloring, whatever–and that question would pop into my head again. What does “nothing” look like? First, I imagined that it would look black, the black of being deep in a forest at night. But that didn’t seem right, either; black is still “something.” And then, I remember, I realized I was thinking about a much worse question. I wasn’t trying to imagine what the emptiness of space would look like. I was trying to imagine what nothing would look like.

I have that memory, I think, because thinking about that sort of broke my brain. I couldn’t comprehend what nothing is.

That question, of course, begins down toward the central question of what our universe is and how it was created. I think that’s why space–the planets, stars, galaxies–so fascinated me then; it’s this thing so alien to our world, that dwarfs it on a scale that’s incomprehensible to us, and yet it is us. We aren’t something held apart separate from it, but intimately a part of it and its history.

Trying to understand the physics of our universe, its structure and history is also an attempt to understand ourselves. I think, at some gut level, I understood that as a kid.

I poured myself into learning about our solar system and galaxy. My parents’ Windows PC had Encarta installed, and I was enthralled. I spent countless hours reading everything I could find within Encarta (which, at the time, felt like a truly magical fount of knowledge) about Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune and Pluto. And when I exhausted that source, I asked for books about space, and I obsessed over them. They were windows into these incredible places, and I couldn’t believe that we were a part of such a wondrous universe.

Through elementary school, my love for space continued to blossom. Then, NASA were my heroes. To my eyes, they were the people designing and launching missions across our solar system so we could understand even more about it. Many of the photos of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune that I was so enraptured by were taken by spacecraft designed, built and launched by people at NASA. They were the people who had risked their lives to leave Earth and go to the Moon, to do something that most people up until just decades prior couldn’t even imagine as being possible. And they were the people who were exploring Mars with a little robotic rover called Sojourner that very moment.

They were my heroes because they were the people pushing us to explore our solar system, to learn what was out there and what came before us. I felt like I was at living during a momentous time in the history of humanity, and that I would live to see advances as incredible as 1969′s Moon landing. There wasn’t a doubt in my mind.

That year, in 1997, I was nine years old. It’s been seventeen years.

Since then, we have indeed made great advances. In that time, we’ve sent three separate rovers to Mars, and we discovered that Mars certainly had liquid water on its surface long ago in its history. We landed a probe on the surface of Saturn’s moon Titan, which sent back these photos. We’ve discovered that our galaxy is teeming with solar systems.

All truly great things. But we are no closer today to landing humans on Mars than we were in 1997. In fact, we are no closer to putting humans back on the Moon today than we were in 1997.

Some people would argue that’s nothing to be sad about, because there isn’t anything to be gained by sending humans to Mars, or anywhere else. Sending humans outside Earth is incredibly expensive and offers us nothing that can’t be gained through robotic exploration.

Humanity has many urges, but our grandest and noblest is our constant curiosity. Through our history as a species, we have wondered what is over that hill, over that ridge, beyond the horizon, and when we sat around our fires, what are the lights we see in the sky. Throughout, someone has wondered, and because they wondered, they wandered beyond the border that marks where our knowledge of the world ends, and they wandered into the unknown. We never crossed mountains, deserts, plains, continents and oceans because we did a return-on-investment analysis and decided there were economic benefits beyond the cost to doing so. We did so because we had to in order to survive, and we did so because we had to know what was there. We were curious, so we stepped out of what we knew into certain danger.

And yet that tendency of ours to risk everything to learn what is beyond everything we know is also integral to all of the progress we have made as a species. While working on rockets capable of leaving Earth’s atmosphere, it would hardly be obvious what that would allow us to do. Would someone then have known that rocketry would allow us to place satellites into orbit which would allow worldwide communication, weather prediction and the ability to locate yourself to within a few feet anywhere on Earth? Economic benefits that result from progress are hardly ever obvious beforehand.