TightWind is written by Kyle Baxter. Stay Hungry. Stay Foolish.

App Store Economics

December 10th, 2008Today, Iconfactory’s Craig Hockenberry published a piece where he explains how the App Store’s structure encourages “ringtone” applications, or cheap and simple applications, rather than complex and more daring applications. Hockenberry writes:

But what happens when we start talking about bigger projects: something that takes 6 or even 9 man months? That’s either $150K or $225K in development costs with a break even at 215K or 322K units. Unless you have a white hot title, selling 10-15K units a day for a few weeks isn’t going to happen. There’s too much risk.

Raising your price to help cover these costs makes it hard to get to the top of the charts. (You’re competing against a lot of other titles in the lower price tier.) You also have to come to terms with the fact that you’re only going to be featured for a short time, so you have to make the bulk of your revenue during this period.

He is right. After the initial honeymoon period where an application receives buzz across the web and placement in the “new” section in iTunes, applications depend on being listed in the top applications lists for sales. Some developers have described the drop off in sales once their application falls off of these lists as tremendous — sales shrinking into the single digits.

The problem I want to discuss is not that applications are so dependent on the front page of the App Store for sales.1 What I would like to discuss is how the App Store’s current structure artificially encourages low price-points.

The Structure

The App Store has a storefront model — what is listed on the front page, and the top lists, is also what sells well. There is a good reason for modeling the App Store this way, though; because there are so many applications available, it is almost impossible to model it in any significantly different way. It must have a storefront which lists the “top” applications available to be of any use at all.

The issue, then, is what criteria are used to judge whether an application is put on the lists.

The only list I am concerned with is the Paid Apps list (the rest are self-explanatory). The paid list currently ranks applications, as far as I can tell, by unit sales. In an article last month, Tap Tap Tap explain what results:

Think about this simple scenario for a second and it should immediately make sense to you… take an app that’s priced at 99¢ and is selling 1,000 units a day compared to an app priced at $19.99 and selling 999 copies per day. The way the App Store currently works, the 99¢ app would still be ranked higher than the $19.99 app, even though the $19.99 app would be earning over 20 times as much as the 99¢ one!

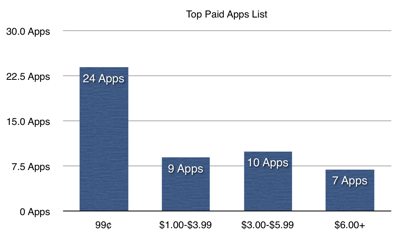

This is pretty simple: lower-priced applications sell more units, so they are listed higher on the top paid applications list. This is bore out by the current top paid applications list, which breaks down in the following way:

99¢ applications account for almost half of the top 50.

If we are only concerned with what applications are absolutely selling more, and the information is in a vacuum, then this is not an issue. But it is. The list has a strong impact on an application’s sales.

In this way, the App Store encourages developers to set low price-points, because sales are so dependent on being listed on the App Store’s lists, and the paid applications list heavily encourages low price-points.

This on the whole creates an artificial pressure for developers to reduce their prices as low as they can, and as Hockenberry fears, this discourages innovation, risk, and long development time. Low price-points create commodities, not the innovation we are used to on the Mac.

This does not necessarily mean the App Store will be the “crapstore” as Tap Tap Tap calls it, but it will mean that we will see more simple, easy to develop (both conceptually and technically) applications, rather than daring new applications which push the platform forward, because those applications depend on higher price margins to make up for high development costs.

This also reduces the ability for independent developers to succeed on this platform. Large development houses have the capital to survive low margins on their products, but independent developers literally live in their price margin — their livelihood depend on strong margins. Even larger “independent” software companies, like Panic, need strong margins to justify developing for the platform. We will see less Daniel Jalkuts, but more Segas, developing for the iPhone platform. That would eliminate one of the greatest attributes of the Mac platform, and it is certainly scary to think about.

Gross Revenue

In November, Tap Tap Tap proposed a simple solution: base the list on gross revenue, not units sold.

I think this makes a lot of sense. Gross revenue is simply units sold times the price. E.g., if your application sells for $10 and you sell 1,000 units, your gross revenue is $10,000.

This is smart to use as a structure. Right now, the App Store encourages low price-points. If gross revenue was used as a criterion rather than units sold, though, developers would be encouraged to balance their price with units sold. The reason is quite simple: they can quickly increase units sold by decreasing the price, but the decreased price balances out the effect.

For example, if I have an application priced at $9.99 and which sells 20 units a day, and I suddenly reduce the price to 99¢, I should see a sudden jump in unit sales. Under the current system, my application should move up the lists correspondingly, all the while increasing sales. In effect, because my sales volume increases as my application moves up the list, I can make up the price drop in sales volume.2 There can be a snowball effect.

But if the system uses gross revenue to judge whether applications are listed or not, and I reduce my price by that much, I will likely still see an increase in sales, but the only way my application will move up the list is if my increased sales are greater than the cost incurred from the price drop. Thus, rather than be encouraged to move to the lowest price-point possible, developers will be encouraged to balance unit sales and the price-point — that is, prices will tend toward their more natural, higher, point.

This will not solve the App Store’s problems entirely. It still needs trials, a clear refund policy and mechanism, and developers still need to stop using the app pages as marketing, but this will certainly help. By using gross revenue, and thus encouraging more natural price-points rather than artificially low ones, the App Store will be a more viable market for small developers, and applications which are attempting to do something new — ones that depend on higher profit margins.

This helps create not only better applications for the end user, but also a platform which can succeed into the future — which is ultimately what Apple, developers and users want.

- Although this is certainly worth discussing. For example, part of the problem here is that the App Store is designed around product pages, rather than company pages. What happens is it is more difficult for consumers to find other applications from the same developer than it is for finding a developer’s other Mac applications. The reason is that Mac developer websites tend to make their other products immediately visible on all pages, whereas App Store product pages do not. [↩]

- This is the best-case scenario, and is certainly not universally true. In fact, as more developers use this tactic, its effect should wear off. [↩]